Making Course Videos and Audio Accessible

Media has the power to transform your classroom by supplementing course materials, sparking discussions, and explaining complex concepts. Videos and audio can make learning more interactive and dynamic while giving you reusable content for future semesters.

This guide will help you create videos and audio that work for everyone in your classroom. You’ll learn practical strategies to make your media more inclusive and discover why accessible design benefits all your students, not just those with specific needs.

Understanding Educational Media

Educational media includes any videos or audio you use for teaching. This could be a lecture recording, an instructional video, or a podcast episode. When designed thoughtfully, these resources can supplement your course materials, promote discussion, provide real-life examples, and free up valuable class time.

The key is keeping things simple and focused. Students learn best when they can control their experience: pausing to take notes, rewinding difficult sections, or reviewing content multiple times. Videos are particularly effective for learning medical procedures, math equations, and counselling techniques because students can rewatch content as many times as needed to fully grasp the concepts being taught (Noetel et al., 2021).

Four Principles for Effective Media

Keep it simple (Coherence): Remove unnecessary information that doesn’t support your learning objectives. Extra stories or decorative elements can distract from your main message (Fiorella, 2021). Review The Coherence Principle video (length 2:34)

Highlight what matters (Signaling): Point to important information, circle key concepts, or use your voice to emphasize critical points. Your gestures and vocal changes help direct student attention. Check out The Signaling Principle video (length 3:48):

Avoid redundancy: Generally, spoken explanations work better than on-screen text with images and narration. Overloading the screen with redundant information can cause cognitive overload (Fiorella, 2021). See the Redundancy video from Wisc-Online (length 2:58):

Break it into chunks (Segmenting): Shorter segments work better than long continuous content. Consider splitting a 60-minute lesson into three 20-minute parts with brief pauses between sections (Knott, 2020). Look at The Segmenting Principle video (length 3:39)

Check Your Understanding

What Makes Media Accessible?

Accessible media is designed so everyone can use it, regardless of their abilities or circumstances. This includes:

- Captions for videos

- Transcripts for audio content

- Clear audio quality

- Simple, direct language

- Good color contrast in visual elements

The goal is ensuring equal access to your educational content. When you design with accessibility in mind from the start, you create better experiences for everyone. Captions and transcripts are recognized as Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and inclusive design because you are composing in multiple media, speech and text, and designing for adaptability and inclusivity (UDL, 2022; The Inclusive Design Guide, n.d.).

Listen to Brenna discuss her first foray into podcasting and how her audio lectures inadvertently made her class more inclusive and accessible (length 1:50).

Please know that you do not have to make all your own videos and audio files! Listen to Jon discuss when to create your own course media and when to use someone else’s!

Check Your Understanding

Why This Matters

Think about curb cuts on sidewalks. Originally designed for wheelchair users, they now help parents with strollers, delivery workers, and anyone with mobility challenges. Accessible design benefits everyone, not just people with disabilities.

The same principle applies to course media. Captions help students who are deaf or hard of hearing, but they also help anyone studying in a noisy environment or whose first language isn’t English. Transcripts allow students to search for specific information or study without sound.

Listen to Jamie’s story about her struggles in the classroom and her first experience with captions (length 5:42)!

Inclusive design acknowledges the essential nature of accessibility and proactively seeks to provide user-friendly experiences for people with and without disabilities.

(Phillips & Colton, 2021)

Listen to Brenna Clarke Gray discuss thinking a little differently about how accessibility and accommodation function (length 5:24).

Here is a link to the full episode: You Got This! Season 3, Episode 13: A Bit of a Pickle, ft. Emilio Porco.

When students cannot access your content, they miss out on learning opportunities. By designing inclusively, you create a more equitable classroom where all students can succeed.

How Accessible Media Enhances Learning

Accessible videos and audio improve the learning experience in several ways:

Flexible learning: Students can engage with content at their own pace, reviewing difficult concepts as needed. This reduces cognitive load and helps with comprehension (Fiorella, 2021).

Multiple formats: Providing the same information through different channels (visual, auditory, text) helps students with different learning preferences and needs.

Better engagement: When students feel included and can access all course materials, they’re more likely to participate actively in learning. Students can struggle emotionally and cognitively when they don’t feel a sense of belonging in the classroom (Bowen, 2021).

Increased comprehension: Captions and transcripts can improve understanding for all students, not just those who need them for accessibility reasons.

Study support: Transcripts can be downloaded, searched, and reviewed offline, giving students more study options.

Check Your Understanding

Creating Accessible Media

Getting Started

Focus on good audio quality first—it’s more important than perfect video. Students need to hear you clearly to benefit from your content. Don’t worry about making everything perfect; authentic, relatable content often works better than overly polished productions.

Adding Captions and Transcripts

For Kaltura users: The system generates automatic captions, but you’ll need to edit them for accuracy. Machine-generated captions often contain errors due to background noise, accents, or technical terms.

Learn how to edit and download captions in Kaltura videos.

You will find comprehensive written instructions for editing captions in Kaltura at Accessibility and Enrichment: Editing Captions.

For YouTube: Use the platform’s automatic captioning feature, then review and edit for accuracy. YouTube provides comprehensive instructions for:

For other platforms: Most screen recording software offers captioning options, or you can add captions during the editing process. If you are on a MAC you may choose to use QuickTime and if you are on a Windows computer you can check out iSpring Free Cam. You could also use Loom which works on any device or you could use paid softwares such as Snagit or Camtasia.

Audio Considerations

If you’re creating audio-only content, always provide a transcript. Consider recording lectures with a simple external microphone connected to your phone, this creates reusable content students can access anytime. For audio editing we recommend Audacity, Audacity is a free, open source software that works on Windows, macOS and many other operating systems.

Best Practices

- Test your content with captions on to ensure accuracy

- Use clear, simple language in both spoken content and captions

- Include diverse representation in your videos when possible

- Keep segments short to maintain engagement

- Provide context when reusing content across semesters

Moving Forward

Start small by adding captions to one video or creating a transcript for one audio file. As you become more comfortable with these tools, you can apply these practices to more of your content.

Remember that accessibility isn’t just about compliance—it’s about creating inclusive learning environments where all students can thrive. When you design with everyone in mind, you create better educational experiences for your entire class.

Recap Key Takeaways

You now have the tools and knowledge to create accessible course media that works for everyone. Let’s recap the key takeaways:

Start with purpose: Keep your videos and audio focused on learning objectives. Remove extraneous content, highlight what matters, avoid redundancy, and break longer content into manageable segments.

Design for everyone: Accessible media isn’t just for students with disabilities—it benefits your entire class. Captions help students in noisy environments, transcripts support different learning styles, and flexible pacing allows everyone to learn effectively.

Take practical steps: Focus on good audio quality, add captions to your videos, provide transcripts for audio content, and test your materials to ensure they work as intended.

Remember the impact: When you create accessible media, you’re building a more inclusive and equitable learning environment. Students who can fully access your content are more engaged, more successful, and feel a greater sense of belonging in your classroom.

Your Next Steps

You don’t need to redesign everything at once. Start small:

- Choose one video or audio file from your current course

- Add or improve captions and create a transcript

- Review it using the design principles from this module

- Ask for student feedback on what works well

As you gain confidence with these practices, you’ll find that accessible design becomes a natural part of your content creation process.

Remember: accessible media isn’t about perfection—it’s about intention. Every step you take toward more inclusive course design makes a real difference for your students.

Connection to Competencies

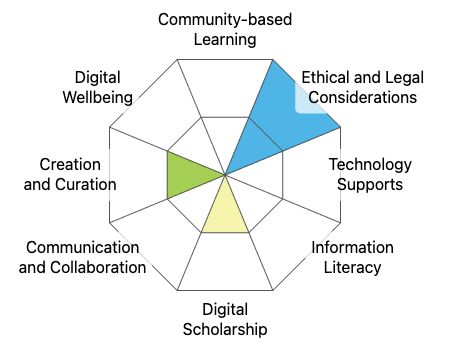

The Making Course Videos and Audio Accessible guide supports the B.C. Post-Secondary Digital Literacy Framework by developing educators’ capacity to create and present accessible, inclusive course materials that prioritize diverse learner needs. By focusing on multimedia accessibility, understanding what it is, why it matters, and how to design course media that aligns with accessibility standards, the module most directly aligns with Ethical & Legal, helping instructors understand their responsibilities to provide equitable access to educational content and comply with accessibility standards. It also enhances Creation and Curation by building practical skills in formatting and structuring course materials for accessibility, and it strengthens Digital Scholarship as participants learn how accessibility features support learning for all students and explore best practices for inclusive digital content design. Together, these competencies help instructors to produce course media that is accessible from the ground up, thoughtfully structured, and designed to serve the all learners in their courses.

Module References

Bowen, J. (2021, October 21). Why is it important for students to feel a sense of belonging at school? ‘students choose to be in environments that make them feel a sense of fit,’ says associate professor Deleon Gray. College of Education News. Retrieved March 20, 2023, from https://ced.ncsu.edu/news/2021/10/21/why-is-it-important-for-students-to-feel-a-sense-of-belonging-at-school-students-choose-to-be-in-environments-that-make-them-feel-a-sense-of-fit-says-associate-professor-deleon-gra/

Fiorella, L. (2021). Multimedia Learning with Instructional Video. In R. Mayer & L. Fiorella (Eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning (Cambridge Handbooks in Psychology, 3rd ed., pp. 487-497). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108894333.050

Knott, R. (2020, March 10). Myth busted: This is the best video length (or is it?). The TechSmith Blog. Retrieved March 16, 2023, from https://www.techsmith.com/blog/video-length/

Phillips, C., & Colton, J. S. (2021). A new normal in inclusive, usable online learning experiences. In Thurston, T. N., Lundstrom, K., & González, C. (Eds.), Resilient pedagogy: Practical teaching strategies to overcome distance, disruption, and distraction (pp. 169-186). Utah State University. https://doi.org/10.26079/a516-fb24.

The UDL guidelines. UDL. (2022, September 2). Retrieved March 3, 2023, from https://udlguidelines.cast.org/

Welcome to the Inclusive Design Guide. The Inclusive Design Guide. (n.d.). Retrieved March 10, 2023, from https://guide.inclusivedesign.ca/